Context

Maximinimus was made as part of the 2024 LaSalle Game Jam, where we were challenged to create a game within a month following the theme: A Matter of Perspective. It won the competition at 1st Place.

My Work On The Game

Assembled a Game Design Document.

Designed a core game loop and central mechanics that were fun, delivered on the theme, and fit within a limited scope.

Designed most challenges and puzzles throughout the game.

Assembled a "gym" to test mechanics, puzzles and levels, and conducted playtest sessions.

Lead multiple playtest sessions, collected feedback, and communicated with team members to incorporate needed changes.

Oversaw the writing and implementation of the narrative script.

Voiced one of the main characters.

For a detailed breakdown of my work, continue below!

Part 1: Pre-Production

Maximinimus was made as part of the 2024 LaSalle Game Jam, where we were challenged to create a game within a month following the theme of: A Matter of Perspective.

As Game Designer, it was my job to conglomerate my 4 person team's many ideas into a cohesive, and importantly fun set of mechanics. In addition, the Jam included a set of Modifiers; further restrictions we could choose to undertake in order to further impress the judges.

The team had settled very early on our idea: a fantasy puzzle game following a duo of opposing sizes. A lumbering giant and a nimble pygmy would take advantage of their dichotomous sizes, skills, and perspectives to delve deep into an ancient dungeon. Settling on this early allowed me to then use the rest of the first day to prepare a rudimentary Game Design Document, forming a cohesive vision and giving the team a unified direction. My primary goal was to outline the core mechanics, the how we'd sell this big and small fantasy to the player, and do so within our limited scope.

Part 2: Designing Core Gameplay

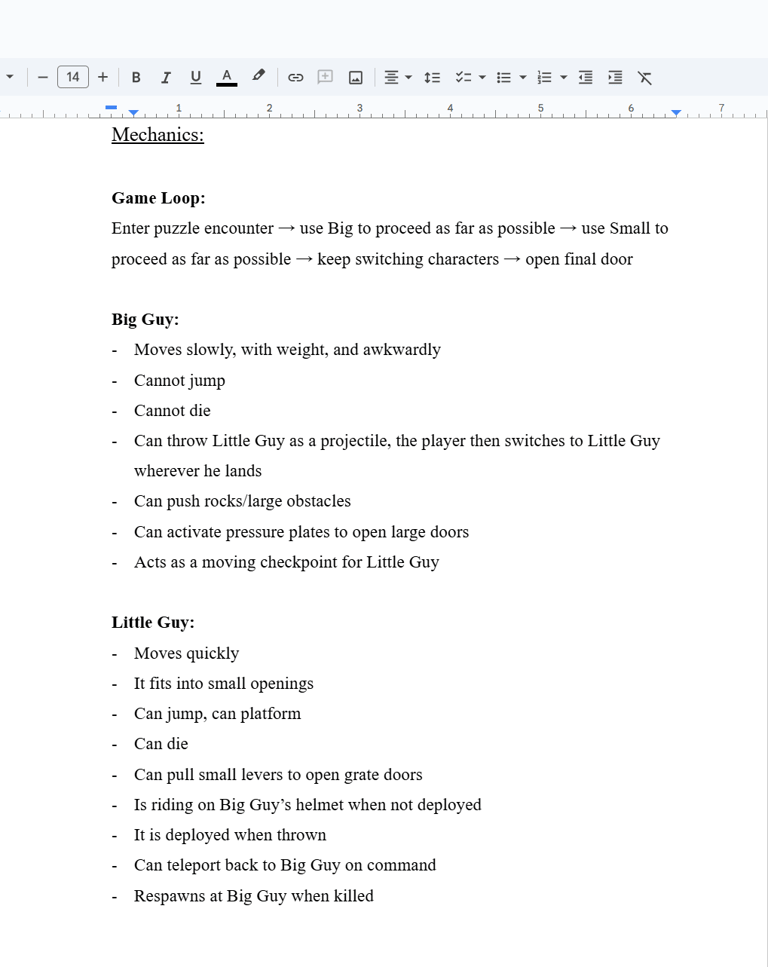

Much of Maximinimus' core identity and design revolves around its characters. Who the player is currently controlling determines how they can interact with the world and progress through the game. This forms the core loop of the game: players must alternate between the characters, using their different abilities in conjunction with each other in order to open a path forward through the puzzles. Here I will display the mechanics of each character and give some insight into my thought process.

Big Guy

My goal when designing Big Guy was not only to have him feel large, but also to use his size to emphasize the teamwork between the two main characters. This lead to the defining (and favourite) mechanic of the game: Big Guy could throw Little Guy. Not only was this hilarious, it was fun, it added verticality, and it served the theme of teamwork perfectly. It also reinforced Big Guy's role as the "pillar" the player relied on. I purposefully designed Big Guy to not be able to die or have his progress regressed in any significant manner, as such he acts as a moving checkpoint that Little Guy can always return to.

Little Guy

I wanted players to be able to take in a level's environment and the elements therein at their own pace before attempting to solve its puzzles. Big Guy's limited movement often makes this difficult, and so I designed Little Guy to provide players with the ability to explore every nook and cranny of a level freely. I think of him as drone that can be deployed almost anywhere (by virtue of being thrown), used to observe a location, interact with it, then be recalled to Big Guy whenever convenient.

Arcana

Arcana was an addition made to our game due to us wanting to take on the challenge of the Who Am I?! Modifier, which required our game to have 3 or more playable characters. It was obvious early on that having three fully fledge characters would be difficult to accomplish successfully, so instead, I cheated a little. Arcana was designed to be more of an additional puzzle mechanic than a full character: players would only be able to take control of her at certain spots, and she would be used to open the path forward before disappearing.

Part 3: Designing Puzzles & Playtesting

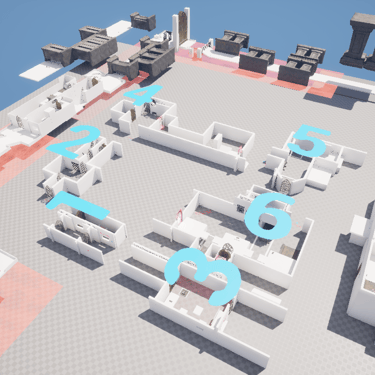

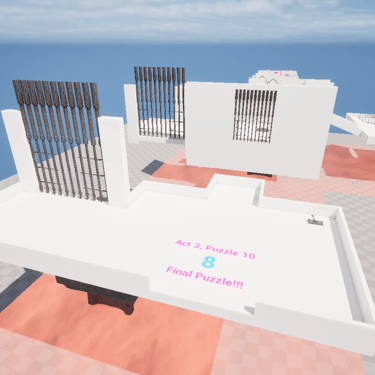

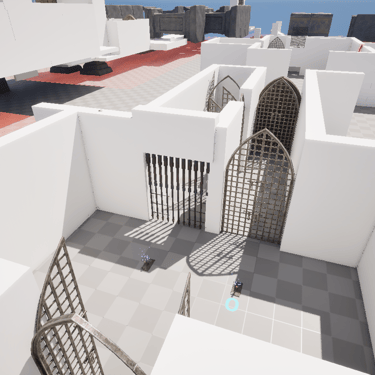

Once the initial designs began being implemented, we needed to see how well these mechanics would come together in an actual level. Despite not being a level designer, I was chosen to take on this task as I best understood how the mechanics should be used. Here's a look into how I built Maximinimus' greyboxes and how they informed my design of the game.

(Click on pictures to expand)

As seen above, I spent most of the development time designing the game's puzzles in a greybox. My goal was to be able to have each puzzle playable as soon as possible in order to get them tested and receive feedback as soon as we could. That feedback would often prompt changes in the puzzle's design, which would once again get tested. My workflow went as follows:

Build puzzle --> Playtest --> Update puzzle based on feedback --> Repeat until desired player experience is achieved --> Approve puzzle for implementation.

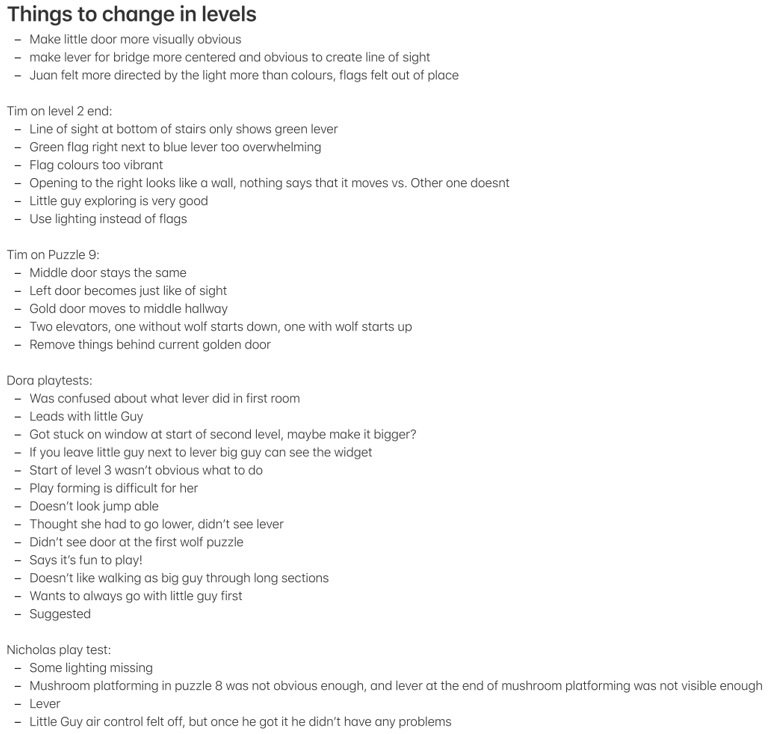

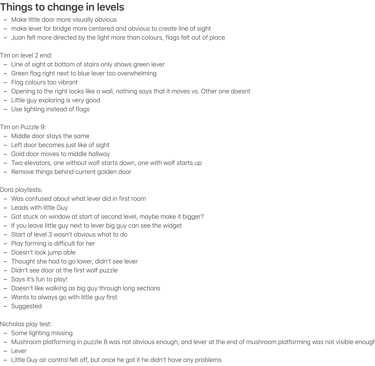

Collecting feedback became an important part of how I approached building these puzzles, as it quickly made clear what was working and what was not. There were many instances of players simply not looking where I intended them to, missing a crucial lever, or simply not understanding what to do. The feedback was not limited to the individual puzzles either, asking the play testers questions after the sessions revealed to us what game mechanics needed change. For example, we planned for levers and the doors to which they were connected to be colour coded through the use of mushrooms and flags. Play testers immediately let us know that this was visually cluttering, and not particularly clear, and so the idea was replaced with better lines of sight and use of lighting.

The image on the right is an example of the notes I would take while observing a play tester, and asking them questions about their experience.

Part 4: Challenges & What I Learned

What shocks me most looking back on the development of this game is how much of it simply went right, we rarely had major challenges or design flaws to overcome. This was no coincidence of course, and I attribute this success to three major factors:

My incredibly talented and hardworking teammates who poured so much of themselves into this project alongside me.

The constant communication we had with each other and trust in our individual work.

The constant feedback we were receiving from our target audience and from our teachers.

Communication is, in short, what I consider to have made this game such a strong project. Looking back at this game, I now ask myself: how can I apply that same level of communication to my next projects?

Maximinimus was made with a small team who would work on the game in person together every day, it was very easy to talk with one another and see what each person was working on, this is sadly not possible on most projects, especially larger ones. In truth, I am still learning how to garner that level of communication across a larger team (see We Three for more details), but what I am now sure of is that play testing works. Not only does it work, but it is a crucial part of any game's design process. In the future, I will always strive to get feedback on my projects as early as possible.

Maximinimus: A Tale of Sizes is the 1st place winner of the 2024 LaSalle Game Jam.